A Financial Perspective on Commercial Litigation Finance

Lee Drucker – 2015 Download PDF

Introduction:

In general terms, litigation finance describes the provision of capital to a claimholder in exchange for a portion of the proceeds from a legal claim (whether by settlement or award) where recourse is limited to the proceeds of the claim at issue.

Legal claims, as an asset (or liability), are similar to a bond or other financial instrument; once a legal claim “matures” through a judicial award or settlement, it entitles the claim creditor to payment on the prescribed terms. Unlike a bond, however, it is uncertain as to whether the asset will indeed mature. A bond entitles the holder to payment on its face. A legal claim must survive the legal system’s crucible to hold any value. Thus, an investment in a single legal claim bears substantial risk.

Litigation finance redistributes this risk to the party that is most willing and able to bear and manage it. The social benefit of this risk distribution is the allocation of capital resources to their highest and best use; allowing companies to invest in projects that optimize returns and promote general economic growth.

This article will examine (i) how a company can benefit from transferring the risk associated with an investment in a legal claim, (ii) why an entity holding a portfolio of legal claims is more capable of bearing and managing such risk, and (iii) why litigation financiers are well suited to aggregate portfolios of legal claims.

Part I: How the Redistribution of Risk Can Benefit a Company

The use of commercial litigation finance enables a company to better manage and finance legal claims, and to improve the productivity of its resources overall. To illustrate, imagine a company faced with the prospect of pursuing a legal claim that has potential damages of $30 million and a 70% likelihood of success. The company would (should) take the following steps when analyzing whether to attempt to monetize the asset:

- Step 1: Estimate the budget for the litigation. The budget should include all fees and expenses through trial, appeal, and collection. For purposes of our example, let’s assume that the total estimated budget is $5,000,000.

- Step 2: Estimate the potential duration of the litigation. This will likely be a function of the complexity of the case as well as the jurisdiction. For this example, let’s assume a duration of three years, which is a common anticipated duration.

- Step 3: Determine the company’s expected return on investment (“ROI”); for a medium to high growth company, an ROI can be expected to be in the range of 30% – 50%.

- Step 4: Calculate the cost to the company of bringing the litigation. Total the cost. This total should include the cost of the litigation plus the lost return on the investment that might have been earned had the company invested in its business.

Based on the assumptions outlined in steps 1 through 3, the cost of allocating resources to the litigation in our example would be between $10,985,000 and $16,875,000.1

Prior to litigation finance, the company would be faced with two choices as to how to invest the $5 million: (i) it could invest it in the operations of the business (i.e., marketing, capital expenditures, research & development, etc.) or (ii) it could invest it in the legal claim. Due to capital constraints the business could not invest in both.

The chart below outlines the potential outcomes for a company without access to litigation finance:

| Decision | Return if Litigation is Unsuccessful | Return if Litigation is Successful | Expected Return (Taking into account probability of loss) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Company Invests the $5m in Operations (Does not invest in the litigation) | $10,985,000 – $16,875,000 | $10,985,000 – $16,875,000 | $10,985,000 – $16,875,000 |

| Company Invests the $5m in Litigation (Does not use that capital for operations) | $0 | $30,000,000 | $21,000,000 |

Note that while the greatest expected return comes from investing in the litigation, it is also the option that bears the most risk; the return profile of the investment in the legal claim is binary, while the return profile of the investment in the business has a probabilistic range of outcomes.

A company with access to litigation finance, however, can monetize a portion of the claim proceeds in order to bring or defend the litigation, and still maintain the necessary capital to invest in the business. As will be discussed in greater detail below, a litigation financier holding a portfolio of legal claims is able to assign a higher value to an individual legal claim than a company holding only one or a handful of legal claims. In this case, a financier might be willing to provide the requisite $5 million investment in return for: (i) return of capital, and (ii) 1/3 of the remaining proceeds.

The chart below outlines the potential outcomes for a company with access to litigation finance:

| Decision | Return if Litigation is Unsuccessful | Return if Litigation is Successful | Expected Return (Taking into account probability of loss) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Company Invests the $5m in Operations (Does not invest in the litigation) | $10,985,000 – $16,875,000 | $10,985,000 – $16,875,000 | $10,985,000 – $16,875,000 |

| Company Invests the $5m in Litigation (Does not use that capital For operations) | $0 | $30,000,000 | $21,000,000 |

| Company Invests the $5m in Operations and Uses Litigation Finance To Fund the Litigation | $10,985,000 – $16,875,000 | $27,651,000 – $33,541,0002 | $22,651,000- 28,541,0003 |

In this scenario, the use of litigation finance is advantageous for the company; it creates the highest expected return and the narrowest range of potential outcomes.4 The company can monetize its claim, and invest in its business. (This holds true for a company defending a litigation as well; the company can optimally protect itself, while continuing to invest in business related projects.)

Another important consideration for a company deliberating between an investment in a legal claim and an investment in its business is the treatment that an investor or the ‘market’ might afford to the proceeds generated from that investment. Many of the businesses that stand to benefit the most from litigation finance are those that are in the growth phase of their lifecycle (with access to medium to high ROI opportunities), and many of these companies are seeking to generate returns by rapidly increasing the company’s valuation. In a buoyant economic environment, companies can reach valuations that are in excess of 20X revenue.5 Proceeds from a litigation, however, are considered non-operating revenues, which are reported on an income statement separate from operating revenues, and generally viewed as a one-time gain rather than recurring profit (the basis for valuation). This means that when considering the impact of an investment on the value of a company, the returns generated from an investment in the underlying business will be afforded greater weight. Let us revisit the chart above in consideration of this fact:

| Decision | Return if Litigation is Unsuccessful | Return if Litigation is Successful | Valuation of Returns if Company Receives 10X Multiple |

|---|---|---|---|

| Company Invests the $5m in Operations (Does not invest in the litigation) | $10,985,000 – $16,875,000 | $10,985,000 – $16,875,000 | $109,850,000 – $168,750,000 |

| Company Invests the $5m in Litigation (Does not use that capital For operations) | $0 | $30,000,000 | $0 – $30,000,000 |

| Company Invests the $5m in Operations and Uses Litigation Finance To Fund the Litigation | $10,985,000 – $16,875,000 | $27,651,000 – $33,541,000 | $109,850,0006 – $185,416,0007 |

As the chart illustrates, the value of the company’s returns are maximized by using litigation finance (~$185 million valuation improvement when using litigation finance compared to ~$169 million by investing in business alone or ~$30 million by investing in litigation alone).

Part II: Why a Litigation Financier is More Capable of Bearing and Managing the Risk Associated with Monetizing a Legal Claim

As illustrated above, litigation finance can help a company optimally allocate resources. This can occur because the litigation financier assigns a higher value to the legal claim than does the company. In the scenario outlined above, the litigation financier is willing to invest $5 million in return for (i) return of capital, and (ii) 1/3 of the remaining proceeds, whereas the CFO of the company may have difficulty rationalizing the same $5 million investment in return for all of the proceeds. This apparent incongruity is explained by the higher value ascribed to the legal claim by the financier. But why is it that the litigation financier assigns a higher value to the legal claim than the company? The answer is that as between the two potential investors in the litigation asset – the company and the litigation financier – the litigation financier has a lower cost of capital.

Cost of capital is the required level of compensation or return necessary for holding an asset. Generally speaking, investors must be compensated for both the time value of money and for the risk that the return on an asset will be lower than the expected return. Assets that hold more risk require higher returns, and bear a higher cost of capital.

The value of an asset and the asset’s cost of capital are inversely related. To illustrate:

If an asset will produce $100 in profit per year, and the cost of capital to finance the asset is 10%, then the value of the asset is $1,000. This is because an investor could buy the asset for $1,000 and earn 10% on the investment each year, and thereby meet the cost of capital.

If an asset will produce $100 in profit per year, and the cost of capital to finance the asset is 5%, then the value of the asset is $2,000. This is because an investor could buy the asset for $2,000 and earn 5% on the investment each year, and thereby meet the cost of capital.

Any given asset will be more valuable to an entity that can hold the asset at a lower cost of capital.

There is a marked difference in the cost of capital to an entity holding a single claim asset and an entity holding a portfolio of claim assets. The logic behind this notion is fairly straightforward: The likelihood that an investment in a single claim will materially deviate from the expected return (in other words, the risk) is significant, while the likelihood that an investment in a portfolio of legal claims will materially deviate from the expected return is slight.

The vast majority of risk inherent in a claim asset is what would be termed in Modern Portfolio Theory as “idiosyncratic risk.” Idiosyncratic risk is asset-specific risk that has little or no correlation with the market and can be mitigated by diversification. By contrast, “systematic risk” (in Modern Portfolio Theory parlance) is risk that is inherent to the entire market or an entire market segment, and cannot be mitigated through diversification.

To illustrate, idiosyncratic risk manifests when a company suffers a major factory closure due to a natural disaster (in which case the price of its stock will likely decline while the rest of the market remains unaffected), while systematic risk manifests when the global economy slows down (in which case the price of a company’s stock will likely decline, but so will the valuation of the market segment).

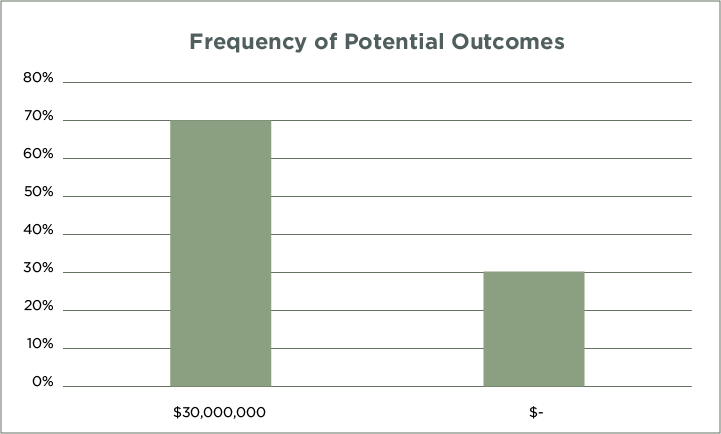

Legal claims possess substantial idiosyncratic risk (each investment has the potential to substantially deviate from the expected return), but virtually no systematic risk (there is little potential for the entire market segment of legal claims to deviate from the expected return). Consider the hypothetical claim that we discussed in Part I. It has a 70% chance of winning, in which case it would yield a $30 million return, and a 30% chance of losing, in which case it would yield a $0 return. Below is a graph representing the potential outcomes of an investment in this claim.

This claim has a high degree of uncertainty. While the expected return is $21 million,8 the company has a thirty percent chance of receiving nothing. This uncertainty is reflected in the asset’s variance or standard deviation of return, a proxy for risk used in Modern Portfolio Theory. Here, it is a virtual certainty that all outcomes will be a significant departure from the mean. In Modern Portfolio Theory, this differential is the definition of risk.

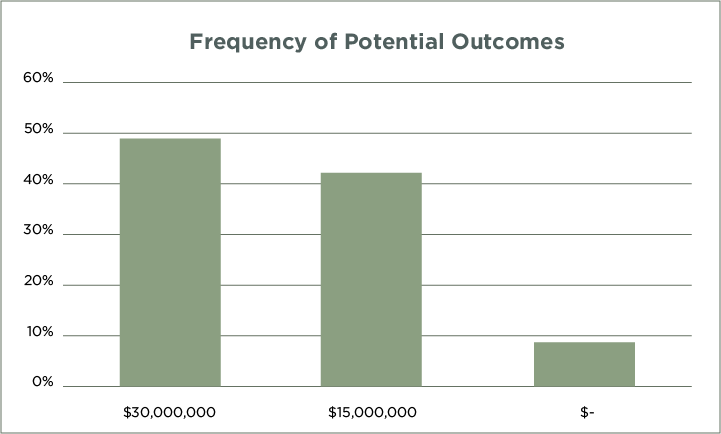

Now let’s explore what happens when we expand the portfolio to include another investment in a legal claim with the exact same return profile (70% chance of returning a $30 million award, and a 30% chance of returning $0).

While the expected average return of each investment in the portfolio is exactly same as it was when there was only one investment in the portfolio ($21M), with the addition of a second non-correlated asset, the chance of yielding a $0 return has dropped from 30% to 9%. In other words, the likelihood of a return that deviates from the predicted mean has decreased, and therefore the returns associated with a two-claim portfolio are less risky than those derived from a single claim.

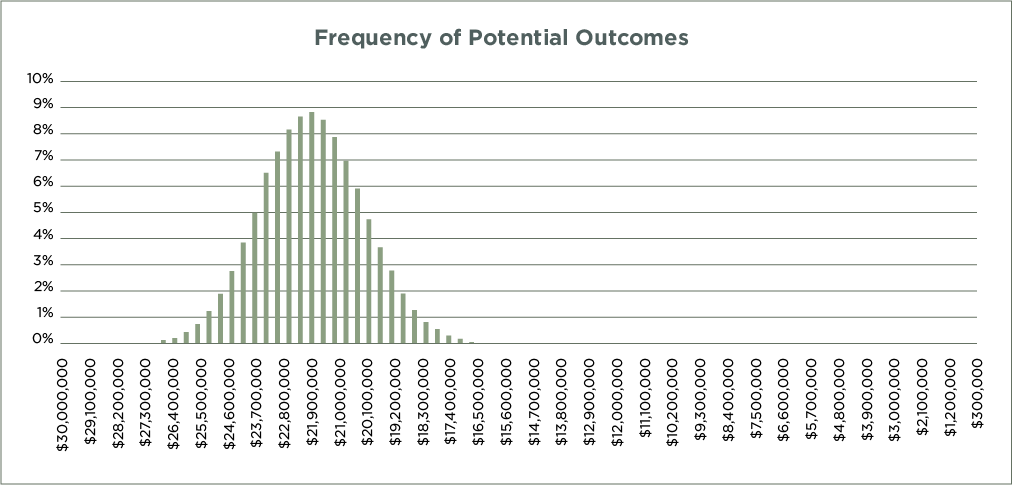

Lastly, let’s examine the return profile of a portfolio holding 100 investments.

This final chart illustrates the power of diversification, and its ability to effectively eliminate the idiosyncratic risk associated with a single claim asset. The expected average return of an investment in this portfolio has not changed from $21 million, but the likelihood of returning anything less than $17M per investment is now less than half of one percent, and there is a ~95% probability that an investment in this portfolio would yield an average return between $18,250,454 and $23,749,545.9

In sum, the aggregation of a diversified portfolio of legal claims precipitously decreases the risk associated with an investment in any single legal claim, and therefore allows an investor to hold the claim asset for substantially less compensation.10 Because an entity holding a portfolio of claims require less compensation (i.e. has a lower cost of capital) for an investment in a claim asset (again, because their risk is lower), the same asset has more value for a financier than it does for a company holding only the individual claim (or handful of claims).

Part III: The Capital Gap

Why have traditional institutions not functioned as a source of lower-cost capital for companies seeking to monetize a legal claim?

Law Firms

While some law firms provide companies with financing in the form of either a full or partial contingency fee arrangement, the availability of this option is nonetheless limited, and law firms are often constrained in their ability to finance a legal claim. These constraints stem from the following:

Regulatory Constraints (Part I): Law firms cannot access the capital markets to raise equity. Professional rules of conduct prohibit lawyers from sharing fees with a non- lawyer. This has created a limiting capital structure as law firms can only rely on business revenues and debt facilities (which typically require regular payments) to fund daily operations and capitalize on growth opportunities. A relatively small portfolio of contingent fee cases, which does not produce regularly recurring revenues, is problematic for large firms that require monthly income to continue operations and that cannot access equity investors to capitalize on growth opportunities. Therefore, it is difficult for most law firms to systematically offer contingent fee arrangements for their clients.

As litigation finance, the profession of aggregating portfolios of legal claims, matures, it seems likely that the cost of capital for a portfolio of legal claims will decrease, and in turn companies will continually be better positioned to nimbly manage their resources and monetize assets related to a legal claim. See https://lakewhillans.com/articles/cost-of-capital-in-litigation-funding/.

Regulatory Constraints (Part II): Law firms cannot provide capital to their clients to help sustain the operations of the underlying business or to hedge risk in the case of a loss. Professional rules of conduct prohibit lawyers from providing financial assistance to a client in connection with a litigation. This directly limits a law firm’s ability to act as a suitable capital source for a claimholder looking to monetize a portion of a legal claim.

Compensation: For the many law firms that do not employ a contingent fee business model, it is difficult to structure a fair annual compensation formula for partners who are working on a contingent basis that is acceptable firm wide. For example, how does a firm determine the relative compensation of two partners; the first partner, a transactional lawyer that has accounted for $5 million in annual net income for the firm; the second partner, a lawyer who spends 100% of her time on a single contingent fee case that has accounted for $5 million in paper losses, but might produce $30 million in net income in three years?

Venture Capital Firms

Venture capital firms invest in early stage growth companies, typically in technology-related verticals such as biotechnology, energy, or software. While top venture capitalists are well positioned to fund promising young companies, and help navigate the pitfalls of growing a company, they are not well equipped to devote fresh capital and resources to defend a portfolio company that finds itself embroiled in litigation. There are several explanations for why a venture capital firm may have difficulty supporting a company in litigation:

- (i) Difficulty Assessing the Prospect of Success: venture investors are often ex- entrepreneurs and/or possess great domain expertise in an area of innovation. Assessing a legal claim is typically not a core specialty and quantifying an investment in a legal claim can be a treacherous endeavor. Outsourcing such a task to a litigator may not be an option.

- (ii) Risk / Reward Calculus May Not Align with Target Investments: venture capitalists make the vast majority of their returns from a few portfolio companies that generate outsized returns. While a portfolio company may have a valuable and meritorious claim, realistic damages are often less than what would have been achieved had the company become a dominant player in the relevant market. Therefore, it may not make economic sense for a venture capitalist to reinvest in a company that has a relatively low ceiling for return when compared to their target investment returns.

- (iii) Fund / Investment Size: many venture capital firms raise relatively small funds (on the order of $100M – $200M). It would be difficult for these firms to invest $5+ million in a legal claim without significantly over allocating the fund’s resources to a single company.

Private Equity Firms

Private equity firms invest in a broad class of companies and employ a wide array of value generating techniques, but like venture capitalists, are not well positioned to support a portfolio company that would benefit from monetizing a legal claim:

- (i) Disciplined Budget: private equity firms typically implement disciplined budget allocations to meet operational and financial targets. Servicing the financial demands of a legal claim is often not within the provided budget of a firm’s portfolio company.

- (ii) Debt Financing: private equity firms often utilize debt in order increase the return on equity. Debt reinforces a portfolio company’s need to maintain a disciplined budget. In this manner, the use of debt serves not just as a financing technique, but also as a tool to force changes in managerial behavior.11 When utilizing debt to such an extent, there is no ability to allocate resources to risky, long-term projects such as one-off litigations.

- (iii) Exit Strategy: private equity firms most typically monetize their investments through some form of divestiture, such as a sale to a strategic acquirer or an IPO. In either case, the sale price of the company is usually based on applying a multiple to the relevant metric (such as EBITA or NOPAT) or valuing the company by a discounted cash flow analysis. In both methodologies, the vast majority of a company’s value is derived from its core earnings. Revenues from a litigation are considered non- operating revenues, which are reported on an income statement separate from operating revenues, and therefore are likely to be discounted by investors as a one- time gain; only increasing the value of the company by the amount received, and therefore creating far less value for the private equity investor.

Litigation Financiers

Litigation financiers, however, are well-positioned to invest in legal claims and thereby aggregate claim portfolios for the following reasons:

- (i) Unlike law firms, litigation financiers are unconstrained by prohibitions against sharing profits. This creates a more flexible capital structure that allows a financier to accept risk and capitalize on opportunity.

- (ii) Unlike law firms, litigation financiers are unconstrained by prohibitions against providing capital to claimholders. This affords financiers the ability to help companies sustain operations and mitigate risk through direct capital infusions.

- (iii) Unlike venture capital and private equity firms, litigation financiers are staffed by professionals who are compensated for their acumen in assessing the value of a claim asset.

- (iv) Litigation financiers are purposefully structured to pursue an investment strategy of monetizating claim assets. Legal claim investments are unique in: size, duration, liquidity profile, investment to return ratio, risk to return profile, and portfolio construction, and unlike other capital sources, litigation financiers are structured with these unique characteristics in mind.

Litigation financiers are most capable of bearing and managing the risk associated with monetizing a legal claim, and therefore best positioned to aggregate legal claim portfolios. As discussed, the aggregation of a legal claim portfolio necessarily lowers the risk associated with investing in a single legal claim, and thereby lowers the cost of capital for that investment. This lower cost of capital is passed on to a company holding a legal claim in the form of the litigation financier ascribing a higher valuation to the asset than could otherwise be ascribed by the company originally holding the asset. Litigation finance provides companies with the opportunity to sell a portion of a claim asset at this higher valuation in order to finance both the cost of monetizing the asset and the company’s underlying business.

- 1. The spread sheet that was used to arrive at this calculation can be found here. For the sake of simplicity, I have assumed that the company will have to reserve for the full amount of the litigation on day one (which would in-fact be the case for the venture-backed, high-growth companies that litigation financiers commonly support).

- 2. (($30M-$5M)*2/3)+Return from amounts invested in operations

- 3. (($30M-$5M)*2/3)*.7+Return from amounts invested in operations

- 4. Narrowest range of potential outcomes measured on a percentage basis

- 5. http://avc.com/2014/12/revenue-multiples-and-growth/

- 6. The lower bound is simply the 10X multiple of the return applied the lower ROI figure + $0 for the litigation

- 7. The upper bound is the 10X multiple of the return applied to the higher ROI figure + the company’s stake in a successful litigation (~$16.67M)

- 8. Award upon success: $30M; award upon failure: $0M; likelihood of success: 70%; 70%*30,000,000 + 30%*0 = 21,000,000.

- 9. To understand the theory behind this calculation see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/68%E2%80%9395%E2%80%9399.7_rule

- 10. As litigation finance, the profession of aggregating portfolios of legal claims, matures, it seems likely that the cost of capital for a portfolio of legal claims will decrease, and in turn companies will continually be better positioned to nimbly manage their resources and monetize assets related to a legal claim. For a fulsome discussion on just how low the cost of capital for financiers may go, see https://lakewhillans.com/articles/cost-of-capital-in-litigation-funding/

- 11. http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~igiddy/LBO_Note.pdf